Abraham Lincoln is widely celebrated for his role in abolishing slavery and preserving the Union during the American Civil War. However, a lesser-known and more controversial aspect of his presidency involves his attempts to resettle free Black Americans in the Caribbean. This historical endeavor, rooted in the complex interplay of abolitionist ideals and racial prejudices of the time, sheds light on Lincoln’s evolving views on race and citizenship.

The Context of Colonization

In the early 19th century, the concept of colonization—the idea of relocating free Black people outside the United States—gained traction among both white abolitionists and African Americans. The American Colonization Society (ACS), founded in 1816, aimed to resettle free Blacks in Africa, specifically Liberia. This movement was fueled by a mixture of humanitarian concern, racism, and practical considerations. Some proponents believed that African Americans would face perpetual discrimination in the United States and could achieve true freedom and prosperity only abroad.

By the time Abraham Lincoln became president in 1861, colonization was a well-established but contentious idea. Lincoln, who initially held moderate views on slavery, saw colonization as a potential solution to the “race problem” in America. He believed that the coexistence of free Blacks and whites could lead to social unrest and that voluntary emigration might offer a peaceful resolution.

Lincoln’s Early Views and Initiatives

Lincoln’s interest in colonization was evident early in his political career. As a young legislator in Illinois, he supported the ACS and advocated for state funding to assist free Blacks willing to emigrate. His famous debates with Stephen A. Douglas in 1858 also reflected his belief that freed slaves could face significant challenges integrating into American society.

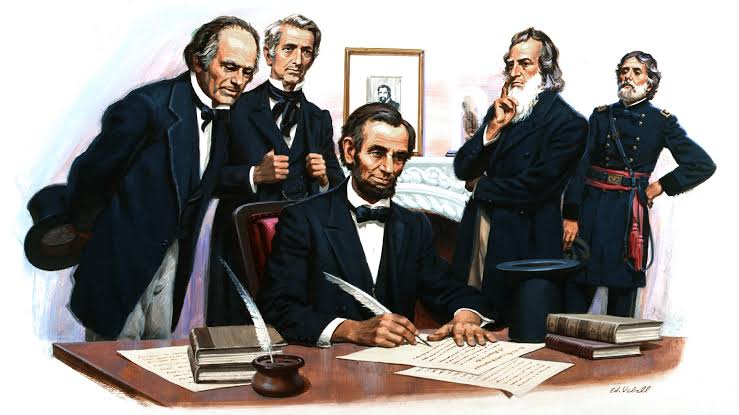

During his presidency, Lincoln pursued colonization more actively. In 1862, he secured Congressional approval for a plan to resettle free Blacks in Central America and the Caribbean. The legislation allocated $600,000 for this purpose, a substantial sum at the time. Lincoln believed that establishing colonies in the tropics could provide free Blacks with better economic opportunities and a chance to develop self-governing communities.

Also, read; House Passes Bill to Automatically Register Young Men for the Draft

The Chiriquí Project

One of the most notable colonization efforts during Lincoln’s presidency was the Chiriquí project. Lincoln’s administration negotiated with Ambrose W. Thompson, an American entrepreneur who owned extensive land in the Chiriquí region of present-day Panama. Thompson proposed establishing a colony for free Blacks on his land, which included rich coal deposits and agricultural potential.

In August 1862, Lincoln met with a delegation of free Black leaders to discuss the plan. He emphasized the potential benefits, stating that emigration could offer a fresh start in a land of their own. However, the response from Black leaders was mixed. Some saw colonization as an opportunity for autonomy and economic improvement, while others viewed it as an attempt to marginalize African Americans and avoid addressing systemic racism in the United States.

Despite initial enthusiasm, the Chiriquí project faced numerous obstacles. Political instability in Central America, logistical challenges, and opposition from Congress and the public hindered progress. By 1863, the project had stalled, and Lincoln began to reconsider the feasibility and morality of colonization.

The Île à Vache Experiment

Another notable attempt at colonization was the Île à Vache project. In 1863, Lincoln’s administration supported an initiative to establish a colony on Île à Vache, an island off the coast of Haiti. The venture, led by entrepreneur Bernard Kock, aimed to resettle thousands of free Blacks. However, the experiment quickly turned disastrous. Poor planning, disease, and inadequate resources led to severe suffering among the settlers. By early 1864, the U.S. government intervened to rescue the survivors and bring them back to the United States.

Lincoln’s Evolving Views on Colonization

The failures of the Chiriquí and Île à Vache projects significantly impacted Lincoln’s views on colonization. By the end of 1863, he began to distance himself from the idea. The issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, marked a turning point in Lincoln’s approach to race and slavery. The proclamation, which declared the freedom of slaves in Confederate-held territories, signaled a shift towards integrating freed slaves into American society rather than encouraging their emigration.

Lincoln’s evolving views were also influenced by the contributions of African Americans to the Union war effort. Black soldiers and laborers played a crucial role in the Union’s victory, challenging the notion that they were unfit for citizenship. By the end of the Civil War, Lincoln had largely abandoned colonization as a viable solution.

Legacy and Historical Perspective

Lincoln’s attempts to resettle free Black Americans in the Caribbean remain a complex and controversial chapter in American history. They reflect the deeply ingrained racial prejudices of the time, even among those who fought against slavery. While Lincoln’s intentions were shaped by the prevailing beliefs and political pressures of his era, his colonization efforts ultimately failed to provide a just solution to the challenges faced by African Americans.

Understanding this aspect of Lincoln’s presidency provides a more nuanced view of his legacy. It highlights the gradual evolution of his views on race and citizenship, culminating in his commitment to emancipation and the integration of African Americans into American society. Today, this history serves as a reminder of the ongoing struggle for racial equality and the importance of confronting and overcoming deeply rooted prejudices.