In the early 19th century, one of the most pressing questions facing American leaders was how to address the issue of slavery. Should the institution continue, or should the United States abolish it? Could the country sustain a population of both free Black people and enslaved individuals simultaneously? If slavery ended, would freed men and women remain in the country or relocate elsewhere? For many white Americans, the answer to this last question lay in “colonization”—sending free Black Americans to Africa.

The American Colonization Society (ACS), founded in 1816 and supported by figures like future presidents James Monroe and Andrew Jackson, sought to create a colony in Africa for free Black Americans. This effort preceded the abolition of slavery in the United States by nearly 50 years. Over the next three decades, the ACS secured land in West Africa, establishing what would become the nation of Liberia in 1847.

The Formation of Liberia

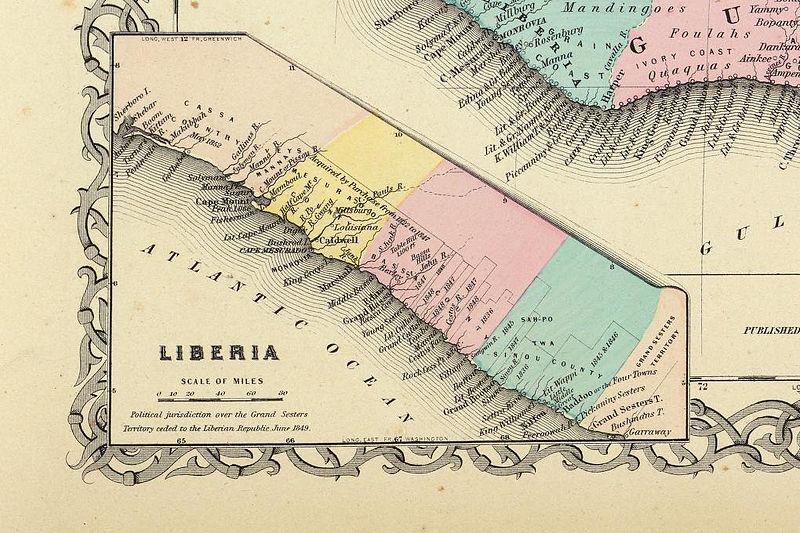

The ACS spent its early years securing land in West Africa. In 1821, it reached an agreement with local leaders to establish a colony at Cape Mesurado. This initial strip of land was just 36 miles long and three miles wide, a stark contrast to modern Liberia, which spans over 38,250 square miles. The following year, the society began sending free people, often in family groups, to the colony. Over the next 40 years, approximately 12,000 freeborn and formerly enslaved Black Americans immigrated to Liberia.

Distinction from Black-Led Movements

The American Colonization Society differed significantly from Black-led “back to Africa” movements that emerged during the same period. These movements, often led by Black Americans themselves, argued that the only way to escape slavery and discrimination was to establish a homeland in Africa. Ousmane Power-Greene, a history professor at Clark University, notes that while some free Black Americans may have supported the ACS’s mission, many others criticized it.

Critics argued that their ancestors’ sweat and blood had built the United States, granting them an inherent right to citizenship. Furthermore, many saw the colonization movement as a scheme by slaveholders to remove free Blacks from the country, thereby reinforcing the institution of slavery.

Also, read; Beyoncé’s Mother Makes Worrying Revelation About the Grammy-Winning Artist

Internal Divisions and Criticism

The ACS itself was not monolithic in its views on slavery. Its members included white men from both the North and the South, with differing perspectives. Some, particularly Southern slave owners, believed that free Black people undermined slavery and should be sent away. Others thought slavery should be gradually dismantled but doubted that Black people could ever live freely alongside white people in America.

As the abolitionist movement gained momentum in the early 1830s, it began to erode the ACS’s support. Unlike the gradualist approach of the ACS, abolitionists called for an immediate end to slavery and viewed the deportation of Black Americans to Liberia as cruel. They argued that sending freed people to a foreign land, where they faced new diseases and a harsh environment, was inhumane.

Lincoln’s View on Colonization

Abraham Lincoln, long before his presidency, expressed support for colonization. In an 1854 speech, he described it as an appealing solution to the moral issue of slavery but acknowledged its impracticality. “If all earthly power were given me, I should not know what to do, as to the existing institution,” he said. “My first impulse would be to free all the slaves and send them to Liberia,–to their own native land. But a moment’s reflection would convince me, that whatever of high hope, there may be in this, in the long run, its sudden execution is impossible.”

The Role of Abolitionists

Abolitionists like Frederick Douglass, Nathaniel Paul, and William Lloyd Garrison played crucial roles in discrediting colonization. Garrison’s 1830s publication, “Thoughts on Colonization,” featured extensive critiques from Black Americans. Abolitionists argued that the colonization movement was inherently anti-Black and incompatible with the goals of true emancipation.

Decline of the American Colonization Society

Throughout the 1830s, the ACS evolved, gradually supporting immediate abolition while continuing to promote Liberia as a destination for free Black Americans. This shift alienated Southern slave owners who remained committed to preserving slavery. By the end of the decade, the society had lost much of its support and financial stability.

In 1841, Joseph Jenkins Roberts, a free-born man from Virginia, became the first Black governor of the colony. Six years later, he declared Liberia’s independence, making it the first African colony to gain independence. The United States, however, did not recognize Liberia as an independent nation until 1862, during the Civil War.

The End of Colonization

Even as late as the Civil War, Lincoln supported voluntary colonization, approving funds for relocating freed individuals to Liberia or Central America. However, he eventually abandoned this idea and began advocating for the integration of Black people into American society, including supporting Black men’s right to vote.

The establishment of Liberia was a significant, albeit controversial, chapter in the history of abolition and colonization. While the ACS’s efforts to relocate free Black Americans to Africa were fraught with challenges and criticisms, they also led to the creation of an independent nation. Liberia’s history reflects the complexities of addressing the legacies of slavery and the struggle for racial equality in the United States.