Three decades ago, two brothers Abdoulaye and Ibrahima Barry; decided their native language needed a new alphabet, because the scripts they’d been using to read and write their native Fulani, an African language spoken by at least 40 million people, weren’t working well.

The brothers hail from the fulbhe/ Fulani ethnic group, who were originally nomadic pastoralists who have spread across West Africa and settled in countries stretching from Sudan to Senegal and along the coast of the Red Sea.

About 50 million Fulbhe people in many African countries speak Fulfulde, also known as Fulani, Fula and Pular. Until recently, they never had a script for their language. Thereby resorting to the use of Arabic and sometimes Latin characters to write in their native tongue.

Neither the Arabic nor the Latin alphabets could accurately spell Fulani words that require producing a “b” or a “d” sound while gulping in air, for example, so Fulani speakers had modified both alphabets with new symbols—often in inconsistent ways.

“Why do Fulani people not have their own writing system?” Abdoulaye Barry remembers asking his father one day in elementary school. The variety of writing styles made it difficult for families and friends who lived in different countries to communicate easily. Abdoulaye’s father, who learned Arabic in Koranic schools, often helped friends and family in Nzérékoré—Guinea’s second-largest city—decipher letters they received, reading aloud the idiosyncratically modified Arabic scripts. As they grew older, Abdoulaye and his brother Ibrahima began to translate letters, too. The Atlantic reports.

“Those letters were very difficult to read even if you were educated in Arabic,” Abdoulaye said. “You could hardly make out what was written.”

The Fulani Adlam Script

So, in 1990, the brothers decided to start working on an alternative. Abdoulaye was 10 years old; Ibrahima was 14.

After school, the two brothers would shut themselves in their room in the family’s house in Nzérékoré, Guinea, and draw on paper, shapes that would make up their new alphabet.

Reports said they would take turns drawing letters, and together, assigned sounds to the shapes they came up with. Within months, they had developed an alphabet with 28 letters and 10 numerals written right to left. They later added six more letters for other African languages and borrowed words, according to Microsoft News.

The brothers started their mission, by first teaching it to their younger sister before teaching people in their community, including the local markets. Students were also asked to teach at least three more people. Then brothers went ahead to further produce their own handwritten books and pamphlets and transcribed books in ADLaM.

Attending university in Conakry, the brothers went ahead to develop ADLaM, and even started a group called Winden Jangen – Fulfulde for “writing and reading” to further their noble course.

However, along the line, Abdoulaye left Guinea in 2003 and moved to Portland with his wife to study finance. But Ibrahima remained in Guinea to complete a degree in civil engineering while still working on ADLaM.

Apart from writing books, he also started a newspaper that had news stories translated from French to Fulfulde. A friend, Isshaga, photocopied these newspapers and Ibrahima distributed them to Fulbhe people, all in an effort to spread ADLaM. But not everyone was happy with the work of the brothers. Critics began to argue, that Fulbhe people should just learn; English, French or Arabic instead of ADLaM.

Challenges

In 2002, Ibrahima was arrested by military officers during a Winden Jangen meeting and he was imprisoned for three months. He was never told why he was arrested and not charged with anything. “Maybe they feared that he was trying to instigate something bigger because they did not understand the script,” Abdoulaye once said.

But, going to jail didn’t deter Ibrahima from continuing his work with the new writing system. In 2007, he also moved to Portland, where he studied civil engineering and mathematics while still writing books.

As time went on, despite some setbacks, ADLaM was spreading beyond Guinea. In Gambia, Senegal and Sierra Leone, a woman who deals in palm oil was already teaching people the writing script. In Nigeria and Ghana, a man who was pleased about ADLaM was teaching others the script.

That was when the brothers knew that their writing system was just about to change lives and enhance literacy among millions of people around the world.

Getting the script on computers

But there was another hurdle. In order to fully achieve their potential, the brothers had to get the alphabet onto computers. They first tried to get ADLaM encoded in Unicode, the global computing industry standard for text, but they were not successful. So, after saving some money, they hired a Seattle company to create a keyboard and font for ADLaM.

“Since their script wasn’t supported by Unicode, they layered it on top of the Arabic alphabet. But without the encoding, any text they typed just came through as random groupings of Arabic letters unless the recipients had the font installed on their computers,” Microsoft News wrote in 2019.

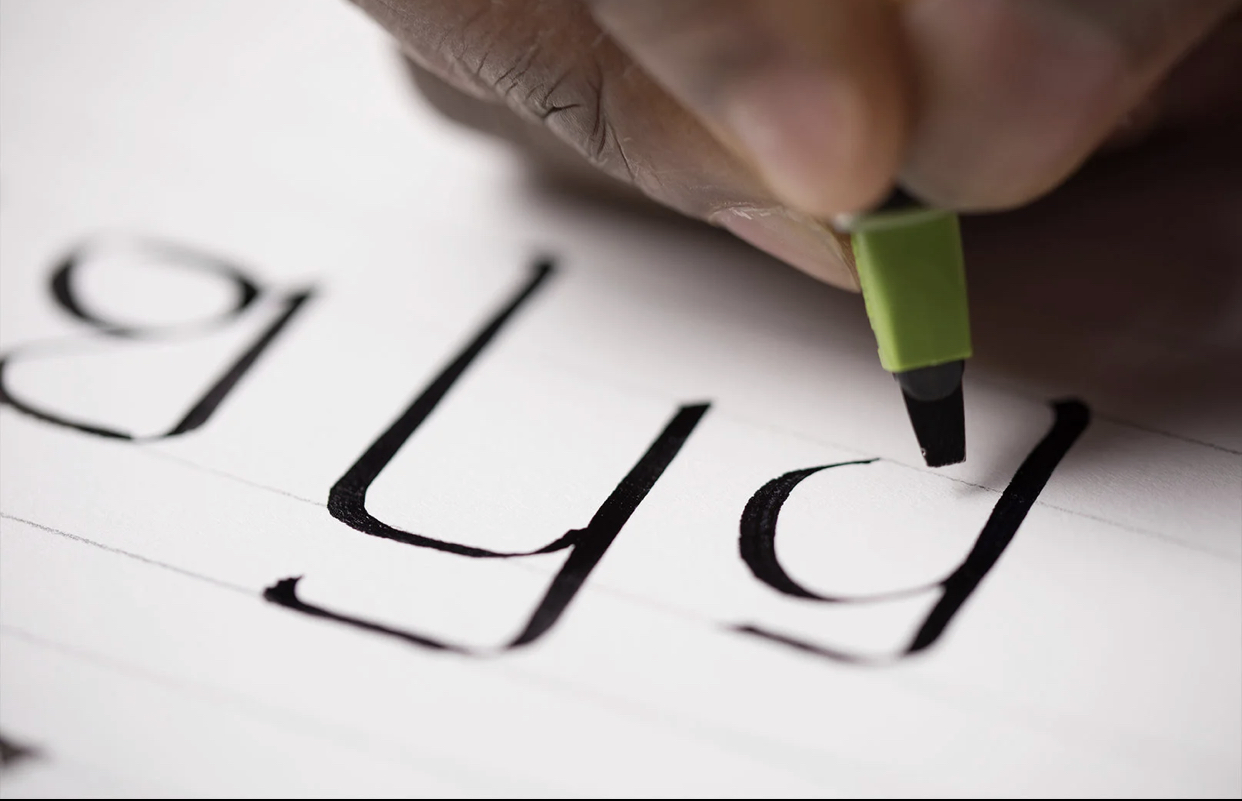

Microsoft’s report said Ibrahima then decided to refine the letters the Seattle font designer developed by enroling in a calligraphy class at Portland Community College.

The instructor, who was moved by Ibrahima’s story, helped him get a scholarship to a calligraphy conference at Reed College in Portland. At the conference, he met Randall Hasson; a calligraphy artist and painter who has also done extensive research on ancient alphabets.

With Hasson’s help, ADLaM became one of the talks at a calligraphy conference in Colorado a year after the two had met. At that conference, Ibrahima got introduced to Michael Everson, one of the editors of the Unicode Standard.

With his help, the brothers put together a proposal for ADLaM to be added to Unicode. In 2014, the Unicode Technical Committee approved ADLaM; and the alphabet was included in Unicode 9.0 and was released in June 2016.

More Challenges For The Fulani Adlam Script

But there was another challenge. The brothers understood that for ADLaM to become usable on computers; it had to be supported on desktop and mobile operating systems. The script also needed to be incorporated on social networking sites in order to increase its reach and make it more accessible.

Andrew Glass, a part of the Unicode Technical Committee and a senior program manager at Microsoft; helped the brothers get the needed support at Microsoft. Eventually, Microsoft developed an ADLaM component for Windows and Office within Microsoft’s Ebrima font; which also supports other African writing systems.

Progress

ADLaM support also got included in the Windows 10 May 2019 update to allow users to type and see ADLaM in Windows, including in Word and other Office apps.

Microsoft’s support “is going to be a huge jump for us,” Abdoulaye, who is now 39, said last year in Portland. At the moment, hundreds of thousands of people around the world have learned ADLaM, and there are ADLaM learning centers in Africa, Europe and the U.S.

Many Fulbhe people, who had never learned to read and write in English or French, are now able to connect around the world and have a sense of cultural pride; said Abdoulaye “Bobody” Barry (not ADLaM’s creator Abdoulaye), who has also learned and taught ADLaM.

“This is part of our blood. It came from our culture,” he said. “This is not from the French people or the Arabic people. This is ours, This is our culture. That’s why people get so excited.”

There are now hundreds of ADLaM pages on Facebook, and people, including children; are learning the script together on messaging apps.

Suwadu Jallow, who emigrated to the U.S. from Gambia, and has learned the script said; “Having this writing system, you can teach kids how to speak (Fulfulde) just like you teach them to speak English. It will help preserve the language and let people be creative and innovative.”