Born into Slavery on the 10th of April 1838, Lucy Higgs Nichols was an African American escaped slave, who became a nurse for the Union Army during the American Civil War. Some sources indicate she was born into slavery in North Carolina and sold to the Higgs family of Tennessee. It was from this Higgs family that Lucy took her last name.

She lived an extraordinary life. Although born a slave in North Carolina, she gained her freedom during the Civil War, became a nurse to the 23rd Regiment of Indiana Volunteers, and lived out her days in New Albany.

Early Life of Lucy Higgs Nichols

Lucy’s early life was filled with uncertainty, because when her owner Rueben Higgs died, she was in an allotment of slaves who were distributed to other family members. She was first sent to Mississippi and allotted to Wineford Amanda Higgs, the only child of Rueben and his first wife Elizabeth. And then, in 1861 upon the death of Wineford she became part of a court ordered settlement that sent Lucy and four other slaves to be divided between Willie and Prudence Higgs. She was then returned to Grays County, Tennessee.

She lived a very disruptive early life of not knowing from day to day if she will see her parents or siblings again. And this was not because of death but the whim of the slave owners. Or as in her case, the courts. The life of the enslaved black people was subject to the whelms of others, families split and living situations that could change from day to day.

Lucy Higgs was handed down to members of that Higgs family until she eventually became the property Willie and Prudence Higgs, who owned a farm near Grays Creek, Tennessee. It was here that Lucy married fellow slave named George Higgs and had a daughter named Mona.

Escape from slavery

In 1862, she gained her freedom by fleeing to the 23rd Regiment while it camped near Bolivar, Tennessee. Lucy with her daughter Mona and group of slaves escaped from Grays Creek, Tennessee by crossing the Hatchie River. They then found their way to Bolivar, Tennessee and arrived behind Union lines.

According to one account, the men of the 23rd protected Nichols and her daughter Mona, when their former owner came after them. She was devoted to the soldiers and they in return were also devoted to her and her infant daughter Mona. As a free citizen Lucy Higgs Nichols worked for the officers and nursed veterans back to health. She also foraged herbs and made medicine for the soldiers.

Lucy Higgs Nichols became a nurse with the 23rd Regiment and remained with them throughout the war. She also participated in at least 28 battles, including the siege of Vicksburg; the capture of Jackson, Mississippi; and the pursuit of Confederate General John Bell Hood in Alabama and Georgia. In addition to serving as a nurse, Nichols also worked for the 23rd Regiment as a cook and servant

Lucy was greatly appreciated and when she contracted measles she was cared for by the soldiers. They also cared for her when she suffered a stroke.

Major Shadrack Hooper of the 23rd Indiana Infantry Regiment d. described Lucy as someone having integrity, honesty, intelligence, always smiling, cheerful and kind, a willing washerwoman, seamstress, nurse, cook and singer as well as a “rattling good forager.”

The soldiers and the regiment surgeon Magnus Brucker described her as a faithful nurse.

Lucy Higgs Nichols was with the regiment when it mustered out in Washington, D.C. She also accompanied the men back to Indiana and settled in New Albany. She was the only woman who served with the 23rd Regiment.

Unfortunately Lucy Higgs Nichols lost her daughter and husband George during the Civil War.

Lucy’s young daughter, died at the Siege of Vicksburg. Although the details of her daughter’s death are not known, the Indiana 23rd Infantry offered her a funeral with flowers.

In the middle of the Civil war, when the regiment went on furlough to New Albany, Indiana, Lucy went with them and was employed as a servant by several officers, including General W. Q. Gresham.

Also, when the Indiana 23rd Infantry were re-deployed to the war in Mississippi, she returned to her nursing duties in service of the Union and was present at every siege. Lucy Higgs Nichols also followed the army east under General Sherman, in The March to the Sea, and then to the north, where the 23rd Infantry was present in the Grand Review of the Armies.

At the wedding of General Gresham’s daughter, Lucy was an invited guest at the Palmer House in Chicago and she was considered one of the family members.

According to reports, there is only 1 known photo of her, and in that photo she is surrounded by veterans of the 23rd Indiana Volunteer Infantry Regiment of the Army of Tennessee, where she served.

The Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) was a fraternal organization which was composed of veterans of the Union Military, which also included the United States Army, Navy and Marine Corps who served in the Civil War. Founded in 1866 in Springfield, Illinois it was made of 100s of posts across the nation. Most of the posts were in the North, but some were in the South and West.

The Grand Army of the republic survived until 1956 when the last member passed.

The Grand Army of the Republic admitted Lucy Higgs Nichols as their only honorary, female member, not only of Sanderson’s Post, men’s group, but of the United States. “Aunt Lucy” as she was affectionately called, was treated as family and loved by all the soldiers that knew her.

Lucy was made an honorary member of Sanderson’s post and never missed a meeting or reunion with the soldiers.

When Nichols became an honorary member of the Sanderson Post of the Grand Army of the Republic (G.A.R.), the major Union veterans’ organization, she was one of a handful of women to receive such status. Higgs also participated in 23rd Regiment reunions, state encampments, and Decoration Day programs, and she also marched with the regiment in parades. Her participation in these activities suggests that she considered her wartime service very significant.

In 1892, Lucy Higgs Nichols applied for her pension from the United States government after Congress passed an act allowing compensation to Civil War nurses. Although she sadly was denied the pension but continued to fight for it.

Many volunteer nurses during the war were denied pensions including Lucy but the GAR rallied to her defense, and she was finally granted a pension as a special act by the Committee on Pensions, July 1, 1898. This subsequently made her famous with many newspaper stories on her and the pension.

She and 55 veterans of the 23rd Regiment petitioned Congress again in 1895. And In 1898, Nichols received her pension through a special act of Congress. For the rest of Lucy’s life she received $12 a month in recognition of her valor during the “War of the Rebellion.”

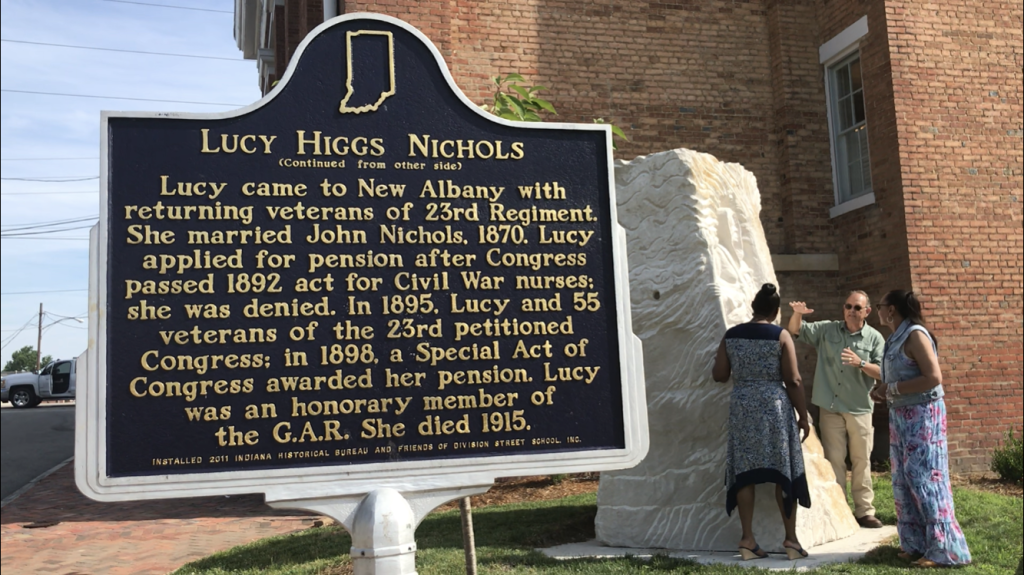

Although Lucy’s accomplishments were buried in archives for more than 100 years, in 1898, newspaper articles, about the special act of congress that granted her pension, spread her fame across the country. These newspapers included The Salem Democrat, Atlanta Constitution, The Logansport Journal, The Denver Post, The Freeman, The Janesville Gazette, and The New York Times. The Lucy Higgs Nichols Historical Marker at Veterans Plaza, at the intersection of East Market and East 10th streets, in New Albany honors her life and role in the struggle for racial equality.

Slave records are often difficult to trace and until recently little was known about her early childhood. However, thanks to the work of New Albany historians, Pamela R Peters, Curtis H Peters, Victor C Megenity—documents have been uncovered showing her being owned as a slave in Hardeman County, Tennessee. The findings have further been published in an article that appeared in Black History Month edition of the Indiana Historical Society’s Traces of Indiana and Midwestern History Magazine – Winter 2010.

And After the war ended, she settled in New Albany, Indiana and found work as a housekeeper working for several of the offers. Despite suffering tragedy, in 1870 she further met and married her second husband John Nichols, a Civil War veteran who had served with the 8th U.S. Colored Heavy Artillery. The couple lived in the Fifth Ward of New Albany with John’s father, Leander. She continued to live in New Albany with her husband John for over 40 years until her death in January 25, 1915.

During her life in New Albany, she was a member of the Second Baptist Church congregation, where her statue was placed in the church’s Underground Railroad Gardens.

Lucy Higgs Nichols spent her last years at the county poor house on Grant Line Road because she had no one to care for her, she died. Lucy’s final resting place is believed to be in West Haven Cemetery.

The statue of Lucy Higgs Nichols

On Wednesday, July 3rd 2019 the Second Baptist Church , also referred to as Town Clock Church, unveiled a sculpture of Lucy Higgs Nichols and her daughter, Mona, which was carved out of nine-foot-tall, 10-ton slab of Indiana limestone.

Talking about the sculpture, “She has a great, unbelievable story,” artist David Ruckman said. “She’s looking for a way to the left, where she’s looking at what might be coming toward her. She can’t afford to get caught. She’s running away to another place. That was New Albany. She is one of New Albany’s residents, and now one of New Albany’s most famous residents. We’re pleased to bring Ms. Lucy to life and bring her back into the sun.”

The installation joins another celebration of Nichols’ life at the nearby Carnegie Center for Art and History. In attendance to witness the unveiling, Director Eileen Yanoviak was in attendance. She called the piece a great addition to the city.

“We’re just so happy that there are so many different ways to share Lucy’s story, whether it’s out in the public environment in the Gardens or in the museum at the Carnegie Center,” Eileen Yanoviak said. “It just shows the commitment to telling her story and to remembering her struggle and tenacity.”

According to Friends of the Town Clock Church treasurer Jerry Finn, the project cost more than $50,000. The organization received a $26,000 grant from Samtec Cares, along with help from other local groups.

The best overview of Higgs’s life is “Remembered: The Life of Lucy Higgs Nichols,” an exhibit at the Carnegie Center for Art and History. The Carnegie Center is located at 201 E. Spring Street and is open Tuesday-Saturday from 10:00 a.m. to 5:30 p.m