Jill L. Newmark, an exhibition specialist at the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health (NIH) in Bethesda, Maryland, describes the first hospital that the US government sponsored specifically to address the health care needs of the former slaves during the Civil War. It was originally known as the Contraband Hospital, but in 1975 it became the Howard University Hospital.

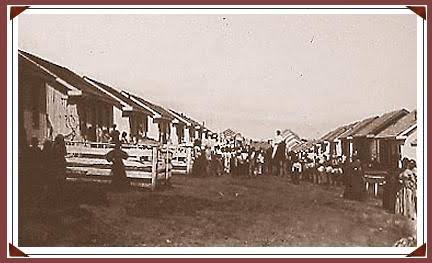

A tented camp and hospital that provided care to hundreds of runaway slaves and black troops during the American Civil War originally stood on a plot of swampy property in northwest Washington, D.C., bordered by 12th, 13th, R, and S Streets N.W. It was referred to as Contraband Camp and housed one of the few black-serving hospitals in Washington, D.C., where the majority of the nurses and doctors were people of African American descent.

After the D.C. Emancipation Act of 1862, which freed all enslaved people in the District of Columbia, over 40,000 escaped slaves sought safety and freedom in Washington, D.C. Thousands of African Americans managed to cross Union lines and become “contraband” as the Union Army moved on southern strongholds. The Federal Government and the Union Army, which were in charge of both the defense of the nation’s capital and the pursuit of victory against the Confederates, faced a conundrum as a result of the growing amount of the so called contraband entering Washington.

How would these African American adults, women, and kids find a place to live, a place to stay, and medical attention? The Union Army created a camp and hospital to assist them in order to handle this task. It turned become a shelter for these former slaves as well as the focal point of government-sponsored relief initiatives for drug traffickers in Washington, D.C.

The Contraband Hospital

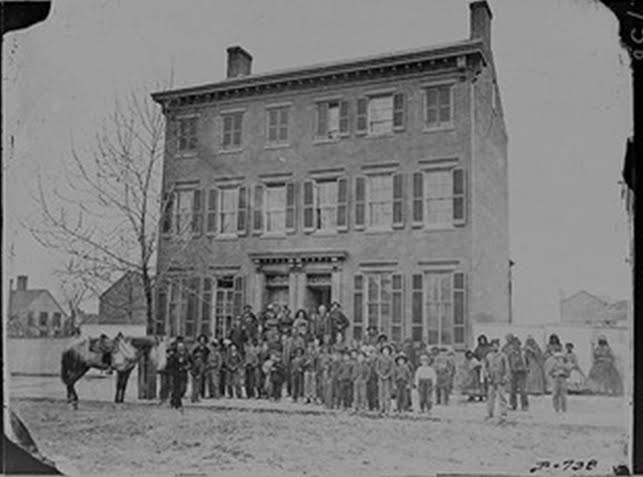

To provide black soldiers and civilians with temporary lodging and hospital wards, the Union Army built the Contraband Hospital and camp as one-story frame buildings and tented structures.

There were created separate tented wards for smallpox victims as well as separate wards for men and women. There were living quarters, a stable, commissary, dead house (morgue), ice room, kitchen, laundry, and dispensary in addition to the contraband hospital wards. By the end of 1863, they had processed over 15,000 people and had 685 residents. Thousands of contraband individuals found refuge and medical attention within the camp.

The camp’s living conditions were subpar and unhealthy. The camp’s poor living circumstances were a result of the soggy, damp land on which it was constructed, a dearth of fresh water, and a sparse distribution of minimal supplies.

The 12 to 14-person occupancy of the small rooms and tents where residents cooked, ate, and slept meant that they frequently caught diseases and ailments as a result of the congested living conditions. Only wooden planks were used as mattresses in tents, and the tents themselves were frequently damaged and tattered, offering little shelter from the wind, rain, and snow. After a strong storm, residents’ clothes and bedding were frequently drenched through. The camp supervisor frequently refused residents supply of blankets, stoves, and other rationed goods, and many tents lacked stoves for heat. As the camp’s primary source of water was a well that was frequently dry, clean water was likewise in short supply.

The Contraband Hospital doctors were well aware of how the water affected campers’ health, but they had little options for improving the situation. The camp became a breeding ground for diseases like diarrhea and respiratory infections due to the moist surroundings and inadequate fresh water supplies.

A mixture of commissioned military troops, civilian employees, and volunteer aid workers made up the Contraband Hospital staff. At least two surgeons, four to six nurses, plus a number of clerks, stewards, and matrons were always on staff.

They gave the hospital’s administration and patient care the vital support they needed to run smoothly. When the hospital opened its doors in 1862, the majority of the chefs, laundresses, and nurses were African Americans, while the majority of the surgeons and head nurses were white.

The first African American surgeon-in-charge, Alexander T. Augusta, was appointed in May 1863, marking the beginning of a change in the contraband hospital staff’s ethnic makeup as blacks replaced whites in positions of leadership.

The first time black people held positions of authority at a hospital in the United States was when African American surgeons and assistant surgeons were appointed. These individuals were commissioned military officers or private physicians working under contract with the army. Alexander T. Augusta, Anderson R. Abbott, John H. Rapier, Jr., William P. Powell, Jr., William B. Ellis, Charles B. Purvis, and Alpheus W. Tucker were some of the medical professionals involved. Because duty stations for these surgeons were at hospitals that only treated African Americans, government records pertaining to their work assignments show that race was the primary factor in their appointment to the hospital. Hospitals with only white patients did not have any black surgeons.

Most of the nurses in the hospital in Contraband Camp were also campers. Washington, D.C.’s metropolitan region had more than 25 hospitals, giving it the largest bed capacity of any city in the Union as well as the biggest demand for nurses and other staff. Newly arrived escaped slaves at Contraband Camp made the hospital an attractive employer for camp inhabitants and an outstanding supply of work for the facility. This easily accessible population could fill hospital roles like nurses, and at the same time, the women and men working as nurses were compensated for their work, assisting in their transition from slaves to paid workers.

Following their escape from the slave owners, many of those recruited as nurses came in the camp unwell and worn out. They were treated for their illnesses in the hospital by people who had gone through a similar ordeal, and the surgeon in charge engaged them as nurses once they had recovered.

Contraband Camp lasted for more than a year before being abandoned in December 1863, but the contraband hospital kept on treating black troops and civilians who needed medical attention. It had relocated from its original location numerous times by late 1864, eventually settling on the site of Campbell Army Hospital, a former army hospital.

From the Contraband Hospital to the Howard University Hospital

In 1865, the Contraband Hospital, now known as Freedmen’s Hospital, officially joined the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, also known as the Freedmen’s Bureau and no longer falling under the command of the U.S. Army. Freedmen’s could provide its patients with better amenities thanks to the shift to Campbell Army Hospital, including a better water supply and waste disposal system as well as a 600 bed capacity. The hospital continued to provide healthcare for the African American community in Washington following the war, eventually relocating to Howard University’s current location in 1868 to serve as the medical school’s teaching hospital.

Although the Civil War was concluded, hundreds of sick and injured people remained in the local hospitals, necessitating the continuous effort of doctors and nurses. The thousands of people who had taken shelter in Washington and were now residing there still required medical treatment. While some of the doctors who had worked in the Contraband and Freedmen’s Hospitals throughout the war sought employment elsewhere, many of them continued their hospital work. Charles B. Purvis started working at Freedmen’s in 1864 as a nurse and, after receiving his medical degree, was promoted to assistant surgeon in 1865. He stayed on staff at the hospital and was appointed chief surgeon in 1881.

Alexander T. Augusta and Alpheus W. Tucker, among other surgeons, later established medical clinics in Washington, D.C. Assuming a post as a professor in the medical school at Howard University, Augusta continued to be associated with the hospital. While some former nurses sought work as domestics in the city, others continued to work at the hospital.

Over the following 100 years, Freedmen’s Hospital continued to provide healthcare services to residents of Washington, D.C., increasing its facilities and accepting both black and white patients. A law legally transferring ownership of the hospital to Howard University was signed by President John F. Kennedy in 1961. Freedmen’s Hospital was renamed Howard University Hospital in March 1975 after relocating to new facilities. It still serves the Washington, D.C., neighborhood today.