A team searching for evidence about the lynching of Black teenager Emmett Till in a Mississippi courthouse basement has discovered the unserved warrant charging a white woman in his 1955 kidnapping, and relatives of the victim want authorities to finally arrest her nearly 70 years later.

A warrant for the arrest of Carolyn Bryant Donham identified on the document as “Mrs. Roy Bryant” was discovered last week by searchers inside a file folder that had been placed in a box, according to Leflore County Circuit Clerk Elmus Stockstill’s statement on Wednesday.

He explained that documents are kept in boxes by decade, but there was nothing else to indicate where the warrant, dated Aug. 29, 1955, might have been. “They narrowed it down between the ‘50s and ‘60s and got lucky,” said Stockstill, who authenticated the warrant.

The search party included members of the Emmett Till Legacy Foundation and two Till relatives: cousin Deborah Watts, the foundation’s head, and her daughter Teri Watts. Relatives want authorities to use the warrant to arrest Donham, who at the time of the slaying was married to Roy Bryant, one of two white men tried and acquitted just weeks after Emmett Till was kidnapped from a relative’s home, killed, and dumped in a river.

Teri Watts said, “Serve it and charge her.”

Keith Beauchamp, whose documentary “The Untold Story of Emmett Louis Till” preceded a new Justice Department investigation that ended in 2007 without charges, was also involved in the search. He stated that there is enough new evidence to charge Donham.

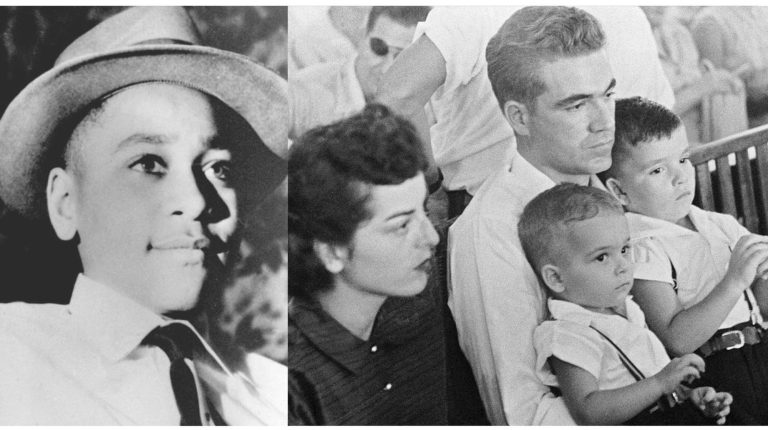

Donham started the case in August 1955, accusing Till, then 14, of making inappropriate advances at her in a family store in Money, Mississippi. Emmett Till’s cousin, Wheeler Parker Jr. who was present said Till whistled at the woman, which defied Mississippi’s racist social codes of the time.

Evidence proposes that a woman, possibly Donham, identified Emmett Till to the men who murdered him. The arrest warrant for Donham was made public at the time, but the sheriff of Leflore County told reporters that he did not want to “bother” the woman because she had two young children to care for.

Donham, who is now in her 80s and lives in North Carolina, has not responded publicly to calls for her prosecution. Teri Watts, however, stated that the Till family believes the warrant accusing Donham of kidnapping constitutes new evidence.

“This is what the state of Mississippi needs to go ahead,” she said.

District Attorney Dewayne Richardson, whose office would prosecute the case, declined to comment on the warrant but cited a December report by the Justice Department on the Till case, which stated that no prosecution was possible.

When reached by the Associated Press on Wednesday, Leflore County Sheriff Ricky Banks stated, “This is the first time I’ve known about a warrant.” When a former district attorney investigated the case five or six years ago, Banks, who was 7 years old at the time Till was killed, said: “nothing was said about a warrant.”

“I will see if I can get a copy of the warrant and get with the DA and get their opinion on it,” Banks explained. If the warrant can still be served Banks said he would have to speak to law enforcement officers in the state where Donham lives.

Because of the passage of time and changing circumstances, arrest warrants can “go stale,” and one from 1955 would almost certainly fail muster in court, even if a sheriff agreed to serve it, according to Ronald J. Rychlak, a law professor at the University of Mississippi.

However, combined with any new evidence, the original arrest warrant, “absolutely” could be an important step toward establishing probable cause for a new prosecution, he said.

“If you went in front of a judge you could say, ‘Once upon a time a judge determined there was probable cause, and much more information is available today,’” Rychlak stated.

Emmett Till, who was from Chicago, was visiting relatives in Mississippi when he entered the store where Donham, then 21, was working on August 24, 1955. Wheeler Parker Jr., Till’s cousin who was present, said that Till whistled at the woman. Donham testified in court that Till also grabbed her and made a lewd comment to her.

Two nights later, Donham’s then-husband, Roy Bryant, and his half-brother, J.W. Milam, arrived armed at Till’s great-uncle, Mose Wright’s, rural Leflore County home, looking for the 14-year-old. Till’s mutilated body, weighed down by a fan, was recovered from a river in another county days later. His mother’s decision to open the casket so Chicago mourners could see what had happened aided the growing civil rights movement at the time.

Bryant and Milam were found not guilty of murder but later admitted to the killing in a magazine interview. Despite the fact that both men were named in the same warrant that accused Donham of kidnapping, authorities dropped the case after their acquittal.

During the murder trial, Mose Wright testified that a person with a voice “lighter” than a man’s identified Till from inside a pickup truck, and the abductors took him away. Other evidence in FBI files indicates that Donham told her husband earlier that night that at least two other Black men were not the right person.