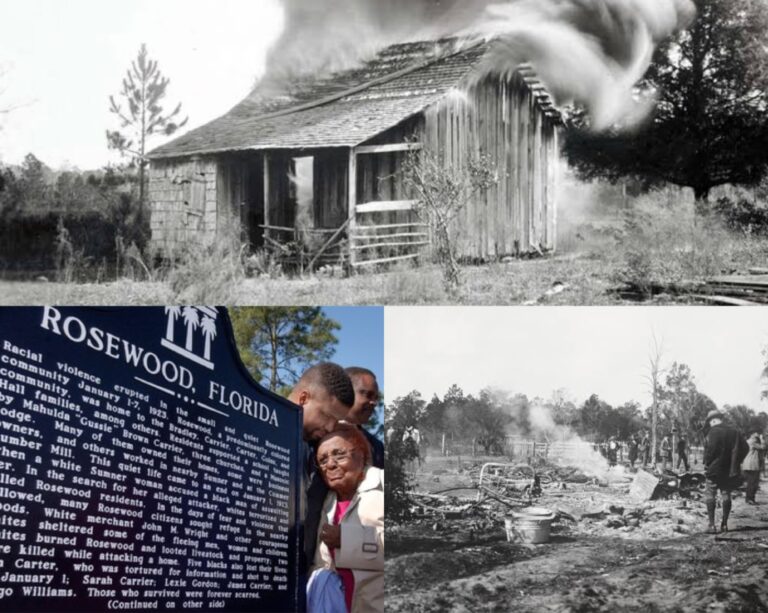

The Rosewood Massacre was a 1923 attack on Rosewood, Florida, which had a substantial African American population, by numerous white aggressors. By the time the conflict ended, the town had been completely devastated, and its inhabitants had been permanently evicted. The tale was largely forgotten until the 1980s, when it was resurrected and made popular.

Rosewood had segregation in the years following the Civil War, despite the fact that both Black and White people originally arrived there in 1845. (and much of the South).

Pencil manufacturers offered employment, but as the population of cedar trees rapidly declined, white families migrated away and settled in the nearby town of Sumner in the 1890s.

There were around 200 people living in Rosewood by the 1920s, and all but one white family—who managed the local store—were Black.

How the Rosewood Massacre Began

A neighbor in Sumner, Florida, heard 22-year-old Fannie Taylor screaming on January 1, 1923. Taylor told the neighbor that a Black male had broken into the home and assaulted her, leaving her covered in bruises.

Taylor specifically stated that she had not been raped when she reported the event to Sheriff Robert Elias Walker.

James Taylor, a foreman at the nearby mill and the wife of Fannie Taylor, inflamed the situation by assembling a horde of furious white residents to find the offender. Additionally, he appealed for assistance from white citizens of nearby counties, including some 500 members of the Ku Klux Klan who were in Gainesville for a demonstration. The local forests were patrolled by white mobs looking for any Black men they could discover.

When the police learned that a Black prisoner by the name of Jesse Hunter had broken free from a chain gang, they instantly called him a suspect. Hunter was the target of the rioters’ attention themselves because they believed the Black residents were keeping him secret.

Dogs guided searchers to Aaron Carrier’s Rosewood home. Sarah Carrier, who washed Taylor’s clothes, had a nephew named Carrier.

Carrier was carried by the white males from his home, shackled to a vehicle, and taken to Sumner, where he was freed and assaulted.

Carrier was put under the protective custody of the sheriff in Gainesville after Sheriff Walker intervened and put him in his car.

When a second mob arrived at the home of the blacksmith Sam Carter, they tortured him until he confessed to harboring Hunter and promised to lead them to the hiding place.

Hunter failed to show up, so someone in the mob shot Carter after he had led them into the woods. Before the mob left, his body was hanging from a tree.

Black employees were encouraged to remain at their places of employment by the sheriff’s office for safety after attempts to disperse white rioters failed.

When armed white men besieged Sarah Carrier’s house on the night of January 4 on the mistaken belief that Jesse Hunter was hiding there, up to 25 individuals, mostly children, had sought safety there.

In the subsequent altercation, shots were fired; Sarah Carrier was struck in the head and died, and her son Sylvester also perished as a result of gunshot wounds. Also killed were two white assailants.

The standoff and gunfight continued all night. When white assailants broke down the door, it came to an end. The kids inside the house made their way out the back and into the woods, where they hid before making their way to safety.

The Violence Escalates

Newspapers falsely reported that groups of armed Black people were going on the rampage and exaggerated the number of those killed as word of the siege at the Carrier house spread. White men continued to swarm the area, thinking that a race war had broken out.

The churches in Rosewood were were of the initial targets of this incursion and were destroyed by fire. After that, people were shot as they attempted to flee from burning houses after which houses were set on fire.

According to History.com, Lexie Gordon was one of those murdered, taking a gunshot to her face as she hid under her burning house. Gordon had sent her children fleeing when white attackers approached but suffering from typhoid fever, she stayed behind.

Many Rosewood citizens fled to the nearby swamps for safety, spending days hiding in them. Some attempted to leave the swamps but were turned back by men working for the sheriff.

James Carrier, brother of Sylvester and son of Sarah, did manage to get out of the swamp and take refuge with the help of a local turpentine factory manager. A white mob found him anyhow and forced him to dig a grave for himself before murdering him.

Others found help from white families willing to shelter them.

Thanks to John and William Bryce, two affluent brothers who owned a railroad, several Black women and children were able to flee.

The brothers drove their train to the area, where they invited evacuees and were aware of the violence in Rosewood. However, they refused to take in Black men because they were worried about being attacked by white mobs.

Numerous people who escaped by train had been hiding out in the white general store owner John Wright’s house throughout the unrest. The Bryce brothers helped Wright organize an escape after Sheriff Walker assisted panicked locals in finding Wright.

Florida Governor Cary Hardee offered to send the National Guard to help, but Sheriff Walker declined the help, believing he had the rosewood massacre situation under control.

Mobs began to disperse after several days, but on January 7, many returned to finish off the town, burning what little remained of it to the ground, except for the home of John Wright.

A special grand jury and a special prosecutor were appointed by the governor to investigate rosewood massacre. The jury heard the testimonies of nearly 30 witnesses, mostly white, over several days, but claimed to not find enough evidence for prosecution.

The surviving citizens of Rosewood did not return after the Rosewood massacre, fearful that the horrific bloodshed would recur.

The Rosewood Massacre Legacy

The story of the Rosewood massacre faded away quickly. Most newspapers stopped reporting on it soon after the violence had ceased, and many survivors kept quiet about their experience, even to subsequent family members.

It was in 1982 when Gary Moore, a journalist for the St. Petersburg Times, resurrected the history of Rosewood through a series of articles that gained national attention.

The living survivors of the Rosewood massacre, at that point all in their 80s and 90s, came forward, led by Rosewood descendant Arnett Doctor, and demanded restitution from Florida.

The action led to the passing of a bill awarding them $2 million and created an educational fund for descendants. The bill also called for an investigation into the matter to clarify the events, which Moore took part in.

Further awareness was created through John Singleton’s 1997 film, Rosewood, which dramatized the events.