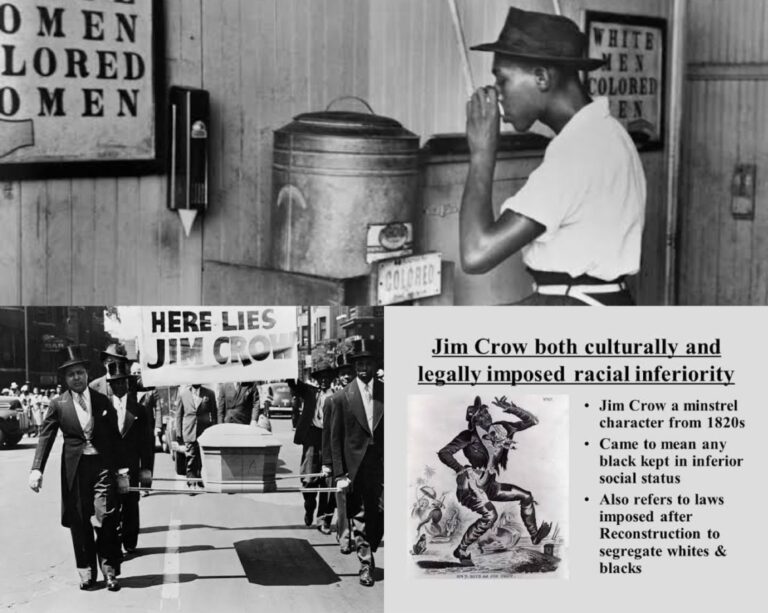

State and local regulations known as the “Jim Crow laws” made racial segregation legal. The laws, which were named after a Black minstrel show character, were intended to marginalize African Americans by denying them the right to vote, hold jobs, receive an education, or have other opportunities. They were in place for about 100 years, from the post-Civil War era until 1968. Jim Crow laws frequently resulted in arrests, fines, jail terms, violence, and even death for anyone who tried to violate them.

The 13th Amendment, which ended slavery in the United States, was ratified in 1865, which is when the origins of Jim Crow legislation first appeared.

Black codes were stringent local and state restrictions that outlined when, where, and how people who had formerly been in slavery might work, as well as how much they could be paid. The codes spread throughout the South as a legal means of enslaving Black people, removing their right to vote, controlling where they lived and traveled, and kidnapping children for labor.

Former Confederate soldiers serving as police and judges stacked the deck against Black citizens, making it challenging for them to prevail in court and guaranteeing that they were bound by Black Codes.

The prison labor camps, where inmates were treated like slaves, operated in tandem with these codes. Black offenders frequently did not serve out their entire term due of the arduous labour and harsher sentences they received than their white counterparts.

According to History.com, during the Reconstruction era, local governments, as well as the national Democratic Party and President Andrew Johnson, thwarted efforts to help Black Americans move forward.

Violence was on the rise, making danger a regular aspect of African American life. Black schools were vandalized and destroyed, and bands of violent white people attacked, tortured and lynched Black citizens in the night. Families were attacked and forced off their land all across the South.

The most ruthless organization of the Jim Crow era, the Ku Klux Klan, was born in 1865 in Pulaski, Tennessee, as a private club for Confederate veterans.

The KKK grew into a secret society terrorizing Black communities and seeping through white Southern culture, with members at the highest levels of government and in the lowest echelons of criminal back alleys.

The Expansion of the Jim Crow Laws

Large Southern cities were not entirely subject to Jim Crow laws at the beginning of the 1880s, and Black people found more freedom there.

Subsequently, large Black populations moved to the cities, and as the decade went on, white city dwellers demanded more laws to restrict the opportunities available to African Americans.

Jim Crow laws eventually swept over the country with even greater force than earlier. African Americans were prohibited from entering public parks, and restaurants and theaters were separated.

It was necessary to have separate waiting areas in bus and train stations, as well as at water fountains, restrooms, building entrances, elevators, cemeteries, and even cashier windows in amusement parks.

African Americans were prohibited from residing in white communities by law. Public swimming pools, phone booths, hospitals, asylums, jails, and assisted-living facilities for the aged and disabled all had segregation policies in place.

Some states mandated that Black and White pupils use different textbooks. The segregation of prostitutes based on race was required in New Orleans.

African Americans in Atlanta were given a different Bible to swear on in court than white people. In the majority of Southern states, it was strictly prohibited for white people and Black people to get married or live together.

African Americans were frequently warned by signs put at town and municipal lines that they were not welcome.

As the 20th century progressed, Jim Crow laws flourished within an oppressive society marked by violence.

Following World War I, the NAACP noted that lynchings had become so prevalent that it sent investigator Walter White to the South. White had lighter skin and could infiltrate white hate groups.

In 1919, a time period that is sometimes referred to as “Red Summer,” there were at least 25 race riots across the United States over a number of months as lynchings soared. White authorities retaliated by accusing Black communities of plotting to overthrow white America.

The Great Migration of the 1920s saw a significant exodus of educated Black people from the South due to Jim Crow dominating the landscape, attacks on education intensifying, and a lack of opportunities for Black college graduates. This exodus was sparked by publications like The Chicago Defender, which urged African Americans to move north.

White people wanted to outlaw the newspaper, which was read by millions of Southern Black people, and threatened violence against anyone seen reading or spreading it.

After World War II, even Black veterans returning home were met with segregation and violence. The Great Depression’s extreme poverty only served to fuel resentment and increase the number of lynchings.

Jim Crow-style legislation did not exclude the North from them. Some states had laws requiring Black people to own property before they could vote, segregated neighborhoods and schools, and businesses that only catered to white people.

Segregationist Allen Granbery Thurman pledged to ban Black voters from voting when he ran for governor of Ohio in 1867. Thurman was appointed to the U.S. Senate after narrowly losing that political contest, where he fought to repeal Reconstruction-era reforms that benefited African Americans.

Black people frequently found it difficult or impossible to acquire mortgages for homes in specific “red-lined” communities after World War II, and suburban developments in the North and South were built with legal covenants that did not allow Black families.

Isaiah Montgomery

Not everyone battled for equal rights within white society—some chose a separatist approach.

Convinced by Jim Crow laws that Black and white people could not live peaceably together, formerly enslaved Isaiah Montgomery created the African American-only town of Mound Bayou, Mississippi, in 1887.

Montgomery recruited other former enslaved people to settle in the wilderness with him, clearing the land and forging a settlement that included several schools, an Andrew Carnegie-funded library, a hospital, three cotton gins, a bank and a sawmill. Mound Bayou still exists today, and is still almost 100 percent Black.

When Did Jim Crow Laws End?

African American civil rights activism increased after World War II, with an emphasis on ensuring that Black people could cast ballots. Jim Crow laws were abolished as a result of the civil rights movement that was sparked by this.

President Harry Truman ordered military integration in 1948, and the “separate but equal” educational era came to an end in 1954 when the Supreme Court determined in Brown v. Board of Education that educational segregation was unconstitutional.

The Civil Rights Act, which was signed by President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1964, officially put a stop to the segregation that Jim Crow laws had established.

And in 1965, the Voting Rights Act halted efforts to keep minorities from voting. The Fair Housing Act of 1968, which ended discrimination in renting and selling homes, followed.

Jim Crow laws were technically off the books, though that has not always guaranteed full integration or adherence to anti-racism laws throughout the United States.