The Aba Women’s Riot, also known as the Women’s War, was an insurrection in Nigeria during the British occupation to redress social, political, and economic grievances. The protest, led by the rural women of Owerri and Calabar provinces, encompassed women from six ethnic groups. The historic occurrence which happened at the end of 1929, is regarded as the first major challenge to British authority in West Africa during the colonial period, and took months to suppress.

Root of the Women’s War

The roots of the riots evolved from January 1, 1914, when the first Nigerian colonial governor, Lord Lugard, instituted the system of indirect rule in Southern Nigeria. Under this plan British administrators would rule locally through “warrant chiefs,” essentially Igbo individuals appointed by the governor. Traditionally Igbo chiefs had been elected.

Within a few years the appointed warrant chiefs became increasingly oppressive. They seized property, imposed draconian local regulations, and began imprisoning anyone who openly criticized them. Although much of the anger was directed against the warrant chiefs, most Nigerians knew the source of their power, British colonial administrators. Colonial administrators added to the local sense of grievance when they announced plans to impose special taxes on the Igbo market women. These women were responsible for supplying the food to the growing urban populations in Calabar, Owerri, and other Nigerian cities. They feared the taxes would drive many of the market women out of business and seriously disrupt the supply of food and non-perishable goods available to the populace. Thus leading to the Women’s War.

Genesis

A warrant chief, Okeugo, under instructions from the district officer, was making a reassessment of the taxable wealth of the people. In this he attempted to count the women, children, and domestic animals. The rumor ran all through the locality in a few days, that the recently introduced taxation of men was to be extended to women.

The villages and the markets where many thousands, mostly women, come together to do petty trading, sell palm-oil to the small middle-men, was to become a part of taxation. As such, the rumors of taxation moved fast, spreading anger and dismay. It was all the more intense because at that period, the price of palm-produce was falling, and new customs duties had put up the cost of several imported articles of daily use.

The Women became really agitated. “We depend upon our husbands, we cannot buy food or clothes ourselves and how shall we get money to pay tax?— We women, therefore held a large meeting at which we decided to wait until we heard definitely from one person that women were to be taxed, in which case we would make trouble, as we did not mind to be killed for doing so”. One of the women who partook in this historic movement was recorded to have said.

The Revolt

Okeugo, finally decided to send out a representative, Mark Emereuwa, to kickstart the process.

The women’s war sparked after a dispute between a woman named Nwanyiriuwa and the representative of the warrant chief, Okeugo because of his request to declare her possession to be taxed.

As soon as the man entered a compound and told one of the married women, Nwanyiriuwa, who was pressing oil, to count her goats and sheep. She replied angrily, “Are you still counting? Last year my son’s wife who was pregnant died. I am still mourning the death of that woman,Was your mother counted?”

Women’s War

After the heated argument between the two, Which saw them seize each other by the throat, Nwanyiriuwa went to the town square to discuss the incident with other women. Believing that women would begin to be taxed the Oloko women invited other women from other areas, gathering nearly 10,000, to protest against the warrant chief.

Palm Fronds which can signify danger and trouble were quickly shared to the women. The women went to the warrant chief’s house and sang war songs and refused to accept that “the trees that bear fruits” should be taxed.

Ikonnia, Nwannedia and Nwaugo were the leaders of the protest, known for their skills in speaking, their intelligence and their passion and their ability to deescalate tense situations. Also, Nwanyiriuwa played a major role in keeping the protests non-violent, advising woman to sing and dance during protests.

Mobs of women passed shouting and singing about the town, “What is the smell? Death is the smell.” They beat upon the iron-trading stores with their sticks and threatened the traders.

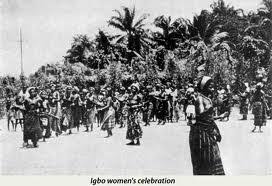

Crowds of women scantily dressed in sackcloth, their faces smeared with charcoal, sticks wreathed with young palms in their hands, while their heads were bound with young ferns protested in several parts of the southern hinterland.

Aftermath

25,000 women were involved in the women’s war, Which was rightly a protest. About fifty-five women were killed and more were wounded by the colonial troops.

The Revolt lasted for two months. November-December 1929.

As a result of the protests, the position of women in society was greatly improved. In some areas, women were able to replace the Warrant Chiefs or appointed to serve on Native Courts. Women’s movements grew stronger in Nigeria, many later events were inspired by these protests.