When Byron Allen first launched a legal rampage back in 2015, few would have guessed he would get to the Supreme Court with a case that could transform the way discrimination lawsuits are handled and represents a coda on 19th century Reconstruction efforts after the Civil War.

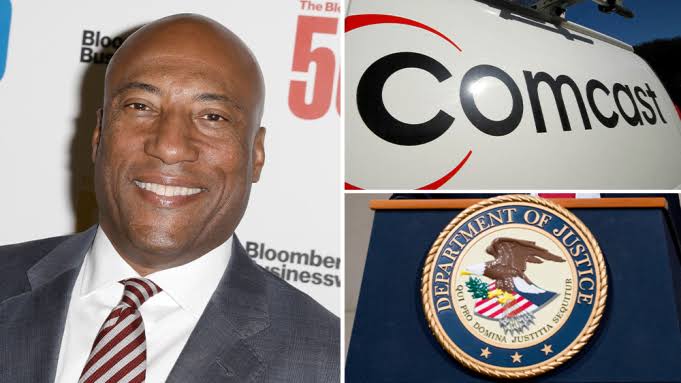

Once known as the entrepreneur who debuted as a stand-up comedian on The Tonight Show as a teenager, Allen, 58, sued cable operators and satellite distributors after they refused to license his small channels devoted to topics including criminal justice, cars and pets. He hired an attorney who defended the city of Los Angeles in the Rodney King beating case and demanded tens of billions of dollars via allegations of a racial bias conspiracy against Comcast, DirecTV, Charter and others.

The Byron Allen Lawsuit

Just how out there was Allen’s lawsuit? The NAACP and Al Sharpton were originally co-defendants in the case for allegedly taking actions to “whitewash” Comcast’s discriminatory business practices. As the story was told in the suit, when Comcast sought regulatory approval for its 2010 bid to acquire NBCUniversal, it looked to gather support. To calm any fears that the merger would have a detrimental impact on diversity, Comcast made voluntary commitments and came to memoranda of understanding with various civil rights groups like the NAACP, National Urban League and Sharpton’s National Action Network. But Allen took issue with those so-called “sham” agreements, questioning the monetary donations that Comcast had made to these groups and further challenging how Comcast was spending $25 billion annually on channel licensing, but less than $3 million on what he characterized as “100% African American-owned media.”

In reviving the case and giving Allen the green light, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals concluded that Allen needed only to plausibly allege that discriminatory intent was a factor in — not the “but-for” cause of — Comcast’s refusal to license his channels. And the appeals court saw enough to meet this standard from the allegation that Comcast was carrying about 500 networks that Verizon, AT&T U-verse and DirecTV were carrying, but unlike its rivals, it did not carry Allen’s. In addition, Comcast was offering carriage to “lesser-known, white-owned networks” like Fit TV, Current TV and Baby First Americas. Comcast may have had legitimate reasons (e.g., no interest in spending millions for Allen’s channel about pets), but the appeals court felt that should be weighed at a latter portion of the case.

The Supreme Court

That the Supreme Court accepted review may be partly attributable to how the business community has locked onto Allen’s dispute with Comcast as an exemplar of tort nuisance. A supporting brief from the U.S. Chamber of Commerce urged the high court to take it up and argued that choices made in the workplace can be “inherently subjective,” and that by making Comcast prove a negative from the get-go — that discrimination isn’t any factor in decision-making — such a standard will impose unwarranted litigation costs and reputational harm on companies throughout the country. Given lingering racial inequity in many walks of life, a standard like the one Allen demands is seen as a threat to the establishment.

If there’s any hope for Allen, it may come from the conservative judicial doctrine of originalism, that being some deeper examination into the intentions of those who drafted the Civil Rights Act of 1866, which followed the formal abolition of slavery through the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Back then, Southern states weren’t happy with the newfound freedom of African-Americans and enacted “Black Codes” to compel them to work through low-wage contracts and debt. Congress responded by passing a federal law aimed at achieving “practical freedom” for ex-slaves, including by prohibiting discrimination when making and enforcing contracts. That included an effort to stop African-Americans from being denied the right to make legitimate contracts. The ambition of the nation’s oldest civil rights statute was a broad stroke striving at equality, with nary a mention of any particular pleading burden.

Both the text of the law and the legislative history are points stressed by Allen, various civil rights groups and a dozen historians opining in this case who believe that reading a “but-for standard” into the anti-bias contracting law threatens to undermine efforts to eradicate racial discrimination.

The list of groups standing behind Allen notably includes the NAACP. That’s right, the same civil rights group once included as a defendant by Allen is now supporting him with an amicus brief. In the history of American jurisprudence, how many times has someone escaped a lawsuit as co-defendant only to turn around and support the plaintiff on appeal? That question should illustrate both the unpredictable road this case has taken and its noble stakes. If the suit struck people as initially outlandish but with a hint of something worth exploring, it well makes perfect sense that Allen’s endeavor has become a vehicle for the Supreme Court to take up standards.

In recent years, the Supreme Court’s growing contingent of conservative justices has acted as a miserly gatekeeper on civil litigation by heightening pleading standards in other contexts, spelling out the requisite injury to maintain a lawsuit and broadly enforcing arbitration agreements. As such, Allen probably goes into the Supreme Court battle, set to be argued Nov. 13, as an overwhelming underdog. The Trump administration is supporting Comcast, led by CEO Brian Roberts, telling the high court there may be repercussions for other federal anti-discrimination laws, too. U.S. Solicitor General Noel Francisco has requested the opportunity to participate in the oral hearings.