Police officers in Chicago will no longer be permitted to pursue people on foot simply because they run away or give chase for minor offenses, the department announced Tuesday, more than a year after two foot pursuits ended with officers fatally shooting 13-year-old Adam Toledo and 22-year-old Anthony Alvarez.

The new policy closely follows a draft policy put in place after those shootings and provides the department with something it has never had before: permanent rules governing when officers can and cannot engage in activities that endanger themselves, those they are pursuing, and bystanders.

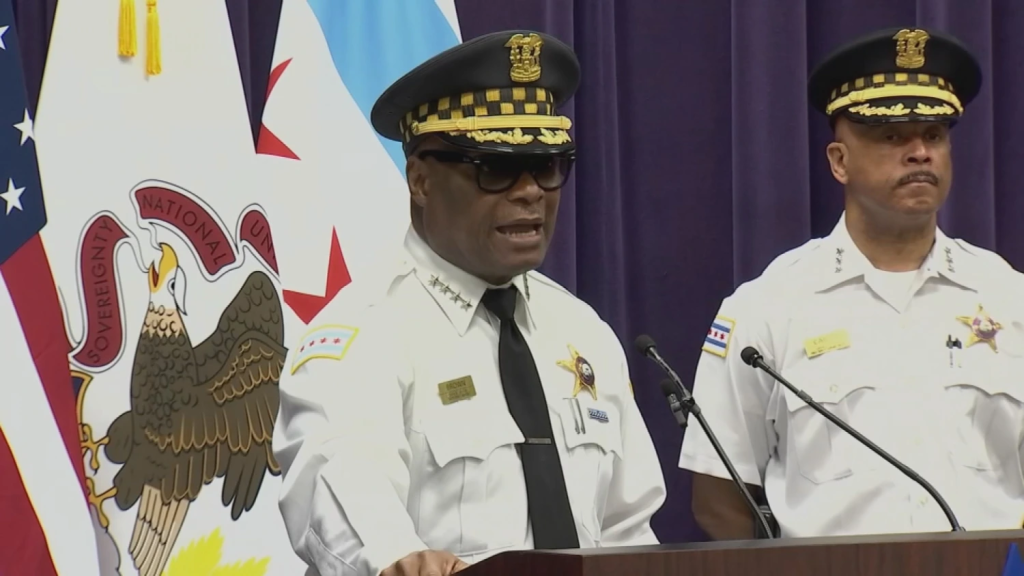

“The safety of our community members and officers remains at the core of this new foot pursuit policy,” said Superintendent David Brown in a statement announcing the policy, which will go into effect by the end of the summer. “We collaborated internally with our officers and externally with our residents to develop a policy we all have a stake in.”

Under the policy, officers may give chase if they believe an individual is committing or about to commit a felony, a Class A misdemeanor like domestic battery, or a serious traffic offense like drunken driving or street racing that could endanger others.

Officers will not be allowed to pursue people on foot if they suspect them of minor offenses such as parking violations, driving with a suspended license, or drinking alcohol in public. They will, however, retain discretion over people they’ve determined are committing or are about to commit crimes that pose “an obvious threat to any person.”

Perhaps most importantly, the policy states unequivocally that the days of officers pursuing people simply because they try to avoid them are over. “People may avoid contact with a member for many reasons other than involvement in criminal activity,” the policy states.

The names of Adam Toledo, 13, and Anthony Alvarez, 22, who were armed when they fled from police in separate pursuits in March 2021, are not mentioned in the policy announcement or the policy itself. However, those pursuits, particularly Alvarez’s, cast a shadow over the policy.

Following the shootings, Mayor Lori Lightfoot demanded that the department develop an interim policy, and the county’s top prosecutor harshly criticized police for the Alvarez pursuit. It also appears that the police department went to great lengths to prohibit that type of foot chase.

The pursuit of Alvarez would not have been permitted under the policy for two reasons. First, when police pursued him for a traffic violation, they knew who he was and where he lived, according to Cook County State’s Attorney Kim Foxx, who announced in March that the officers involved in the two shootings would not be charged. Second, officers are no longer permitted to pursue people on foot who are suspected of the type of minor offense that prompted the chase.

The policy includes a number of situations in which an officer must end a pursuit, including the requirement that the pursuit end if a third party is injured and requires immediate medical attention that no one else can provide. Officers must stop if they realize they don’t know where they are, which is possible in a chaotic situation where they are running through alleys and between houses. And they must stop if they are unable to communicate with other officers, whether because they have dropped their radios or for other reasons.

The policy also emphasizes that officers or their supervisors will not be criticized or disciplined for deciding against or canceling a foot pursuit. Officers are also prohibited from inciting chases, such as by speeding in their squad cars toward a group of people, stopping suddenly, and jumping out “with the intention of stopping anyone in the group who flees.”

Long before the shootings of Toledo and Alvarez, the city had been waiting for a policy.

The US Department of Justice issued a scathing report five years ago, claiming that too many police chases in the city were unnecessary or resulted in officers shooting people they did not have to shoot. Three years ago, a judge approved a consent decree that included a requirement to implement a foot pursuit policy.

The city also had plenty of evidence about the dangers of foot pursuits, including a Chicago Tribune investigation that discovered that one-third of the city’s police shootings between 2010 and 2015 involved someone being injured or killed during a foot pursuit.

Police officials have denied any suggestion that they are dragging their feet, stating that the department has met all deadlines. While Chicago has not taken a lead in the issue, other major cities, including Baltimore, Philadelphia, and Portland, Oregon, have already implemented foot pursuit policies.